第三章:法国大革命如何发展

读 William Doyle 的 “The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction” 所作笔记和摘录,P38-65

原书及其作者:法国大革命,起于捍卫人权、推翻君主专制,却通向了恐怖统治和军事独裁。这个过程值得警醒。

Chp3 How it happened

1. Electoral politics

在三级议会(estates-general)里,教士、贵族、其他所有人,这三个等级各有一张份投票权,不论等级内有多少人。显而易见,在人数上完全少数的教士和贵族可以轻易联合起来达成多数票,而平民等级哪怕占有压倒性的人口数量也只有一张票。

P39-40 By December the clamour against the forms of 1614 was so well established that Necker felt emboldened to act. He decreed that, in recognition of their weight in the nation, the number of third-estate deputies would be doubled. It was obvious that this meant little if voting was still to be by order rather than by head, but Necker believed that the clergy and nobility could be induced to renounce the privilege for themselves once the Estates-General met. He relied on general dissatisfaction with the half-measure of doubling the third to dominate the elections of the spring of 1789 to such a degree that resistance to uniting the orders would become unthinkable. Vote by head was indeed one of the central preoccupations of the electoral assemblies; but since they too were separate, with each order electing its own deputies, the effect was to polarize matters still further. In the face of tumultuous popular support for third-estate aspirations, clerical and noble electors tended to see their privileges as an essential safeguard of their identity; and most of those they elected to represent them were intransigents. Opinion was crystallized further on all sides by the process of drafting cahiers (grievance lists which were also part of the forms of 1614) to guide the deputies chosen. Now emerged questions not only of how the estates were to be constituted, but of what they were actually to do. An amazing range of grievances and aspirations were articulated in what amounted to the first public opinion poll of modern times. Suddenly changes seemed possible that only a few months earlier had been the stuff of dreams; and the tone of the cahiers made clear that many electors actually expected them to happen through the agency of the Estates-General.

2. National sovereignty

上一章结束时已经说明了当时法国的社会问题是病入膏肓的,解法是陈旧不堪的,民意是汹涌动荡、不断自我激化的。三级议会这种制度的代表性问题很快催生了一个新的政治组织,三十人委员会(committee of thirty),并受到他们的抨击。三十人委员会很快又推动了国民议会的出现。

3. The first reforms

国民议会(the national assemble)宣称自己才是国民的合法代表,然而在当时所有人都精神紧张、互不退让、互不信任的局面下,起先的国民议会也一度迟迟无法作为。革命带来的动荡和恐慌传到农村后再传回革命中心,演变成了对原有食税阶层的极度恐慌,更激进的团体和他们破坏社会纤维的大计乘风迅速立上潮头,大受欢迎。

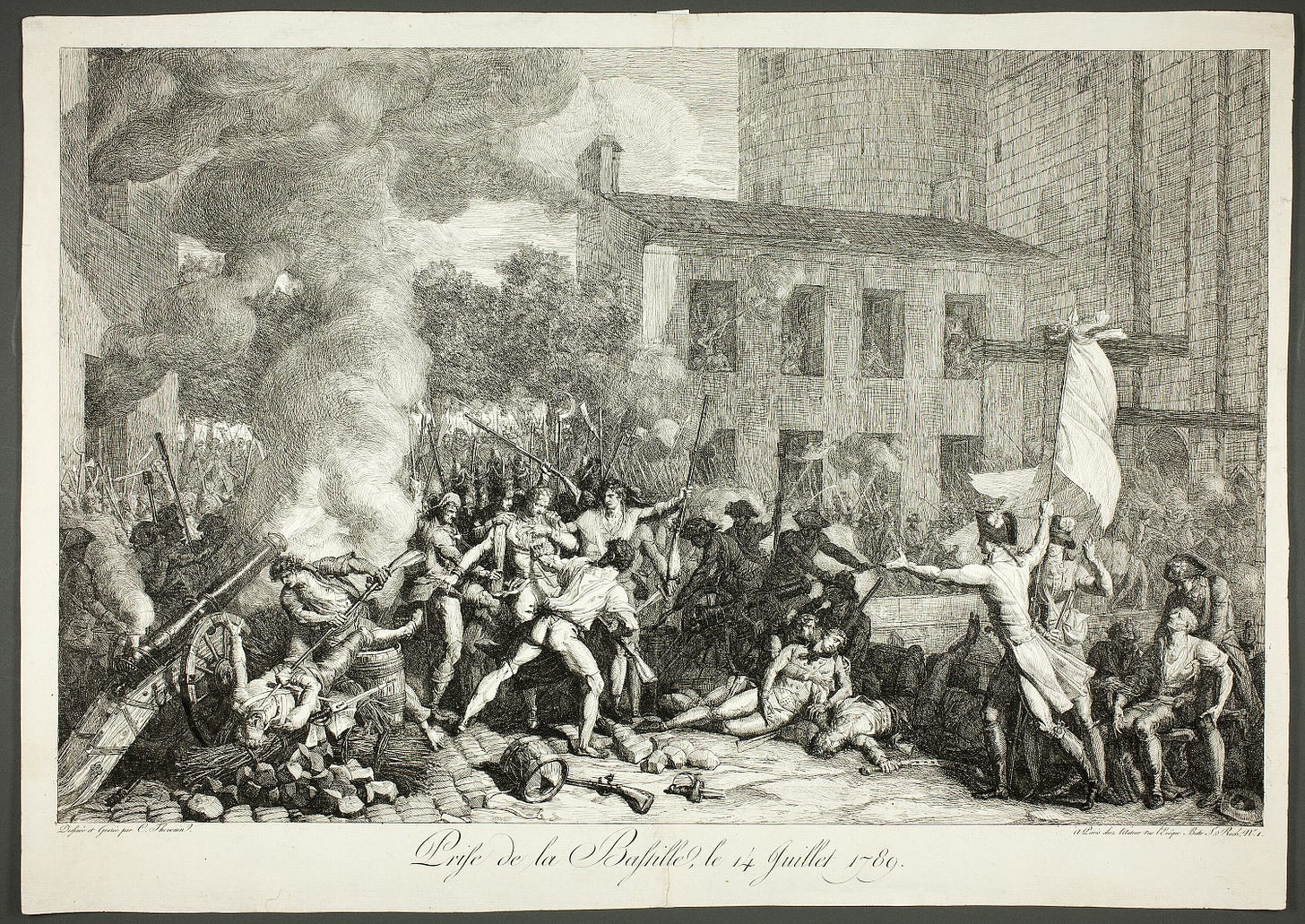

The 14th of July was not, therefore, the beginning of the French Revolution. It was the end of the beginning. P43

和王室冲突频频的国民议会最终得到王室承认,转型为了正式的制宪议会(the National Constituent Assembly),但是擦枪走火终于还是发生了,转型和群众攻占巴士底狱几乎没差几天,法国大革命正式拉开序幕。

4~6. Polarization: religion & monarchy & war

制宪议会制定了君主立宪制的原则和雏形,保留了君主的一定权力。但是这时候的财政灾难还在继续,甚至新账旧账全被翻出来一起算了,社会各方僵持不下、信息不通,加上革命情绪日渐激化、无数大小战争不断逼人选边站,一般争执和行为进退动不动就被上纲上线,试图让政治回归正轨(也有偏袒王室之嫌)的制宪议会很快出局。

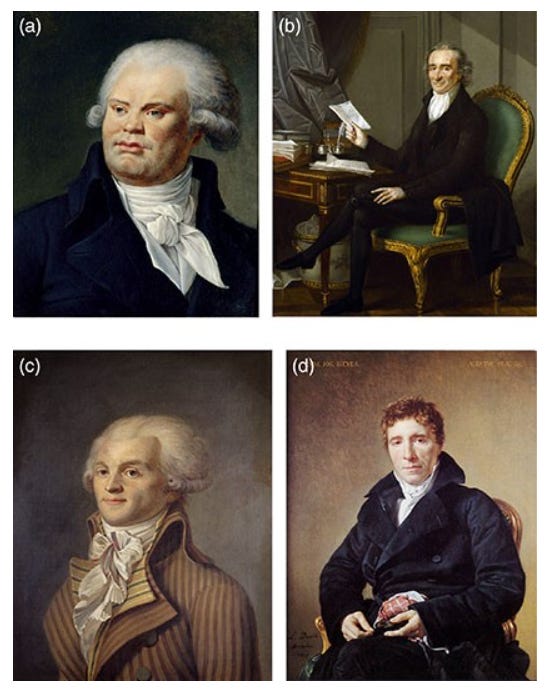

制宪会议在完成宪法起草工作后自行改组形成了更先进的立法议会(the Legislative),但是国王不靠谱国民不买账,立法议会迅速被迫重组为直接普选出的国民公会(the Convention),臭名昭著的雅各宾派在国民公会中声势巨大。社会秩序持续血崩,冤狱、屠杀、混乱、激进化,全都没有停下。合理的声音不是不存在,只是次次都被压过一头,或者自己也倒向激进一派。

P46-48 (制宪议会)Their aim was to set up a constitutional monarchy controlled by the elected representatives of substantial men of property. Their commitment to property owners was also shown in their refusal to renounce the debt bequeathed by absolute monarchy, and indeed a massive expansion of it by promises to compensate all those, such as venal office-holders, whose property would disappear as a result of their reforms. They soon saw that all this could not possibly be met out of taxation. Tax revenues, in fact, were falling catastrophically in the absence of any effective means of coercion. Their solution was to satisfy the nation’s creditors at the expense of the Church. …… Meanwhile counter-revolutionaries were quick to associate their own cause with threatened Christianity. Acceptance of the sacraments from a ‘constitutional’ priest who had taken the oath became a touchstone of loyalty to the entire Revolution. No sincere Catholic could evade this decision; and this included the king.

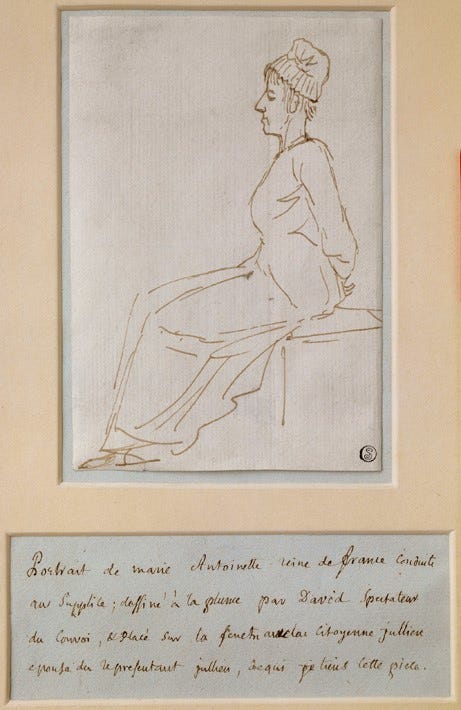

P51 War was the third great polarizing issue of the Revolution. As was intended, it forced everybody to take sides on everything else. It identified the defeat or survival of the Revolution with that of the nation itself, so that critics of anything achieved since 1789 could be plausibly stigmatized as traitors. Most vulnerable to this charge was the king himself, who persisted in his vetoes of laws against refractories and émigrés despite being mobbed in his palace on 20 June by Parisians now calling themselves sansculottes, and wearing red caps of liberty—the ancient headgear of freed slaves.

P52 The full impact and implications of the overthrow of monarchy took the rest of the year to become manifest. Meanwhile the Prussians pushed into France, and Paris remained panic-stricken. A provisional executive council dominated by the Parisian demagogue Danton frenziedly attempted to organize defence with a series of draconian emergency powers which filled the prisons with suspects. As patriotic sansculottes were urged to join up, anxiety spread about a possible prison breakout in their absence. On 2 September, as news arrived that the Prussians had captured Verdun, prisons were broken into and their inmates taken out and massacred. The carnage went on for four days, leaving about 1,400 victims dead, among them many refractory priests. Although the inflammatory populist journalist Marat urged provincial France to follow the capital’s example, news of the massacres horrified opinion both in France and abroad. This was something altogether more serious than the occasional lynchings of 1789 and since, a grim lesson of what happened if the lower orders were not kept under control. Enemies of the Revolution had always predicted bloody chaos; those who wished it well mostly found the massacres equally hard to justify. Everybody in Paris, however, lived henceforth in the fear that they might very well happen again.

7. Civil war and terror

接下来,国民议会自己也开始和民众脱节了。雅各宾派迅速把代表国民变成了,我们代表的才是“真正的”国民,加上当时外部反法联军的军事压力和首领罗伯斯庇尔的个人执念(republic of virtue),迅速走上了血腥打压异见、恐怖统治、拼命征兵、实施戒严、价格管控与余粮收集的道路。权力再次走向了集中、随性、无限制的方向。

P56 The aim of such retribution was as much to terrorize as to punish; and by September the sansculottes, unable to understand why the elimination of their legislator enemies had not produced more positive results, were pressing for terror to be adopted as a principle of government. Intimidated once more by mass demonstrations on 5 September, the Convention reluctantly accepted that it had to be more ruthless. Within a few weeks it had decreed the arrest of all suspects, expanded a revolutionary tribunal established earlier in the year to try political crimes, imposed price controls on all basic commodities (the ‘maximum’), and authorized so-called ‘revolutionary armies’ of sansculottes to force peasants to disgorge their surpluses to feed the cities. The government of the Republic was now to be ‘revolutionary until the peace’—centralized, arbitrary, and armed with emergency powers, all the very opposite of the constitutional conduct of affairs to which the Revolution had committed itself from the outset.

8. The thermidorean dilemma

雅各宾派首领罗伯斯庇尔清完了党外清党内,人人自危,最终他自己也在热月政变中被处死(the Fall of Maximilien Robespierre),雅各宾派垮台,恐怖统治结束。

但战争压力、王室复辟、宗教迫害这三大分歧点仍然存在,现在明摆着高压管控无以为继,所有人都开始对革命感到疲劳。从雅各宾派手里接过大权的热月党人(Thermidorians)将国民公会重组为督政府(the Directory),试图恢复秩序,但基本是使经济等问题直接开始自由落体,内部迅速腐败,并且无力压制保皇派的抬头。

P60 Outside France, the term had become as early as 1790 shorthand for all the Revolution’s excesses. Now it began to acquire the same connotations in France—a legacy of clubs, populism, social levelling, and authoritarianism in the name of these principles, all underpinned by terror. The so-called Thermidoreans in the Convention who had taken over power were committed to dismantling all that had made Jacobinism possible. Thus the prisons were emptied of suspects, the Jacobin club and its affiliates closed, economic controls like the maximum abandoned. The assignats, whose value had been eroded by massive overissue after war broke out, had been somewhat sustained as legal tender by the controlled economy of the Year II: now they went into free fall.

9-10. Napoleon

正当革命形式一团糟,社会失序已久,各个革命派别也走向分裂之时,年轻的拿破仑(Napoleon Bonaparte)开始崭露头角,以一连串的军事成果解了外困,以他的军事手腕再加个人魅力,迅速用横扫一切的独裁掌控了社会,法国进入执政府时期(the Consulate)。

P64-65 He was more than willing to cooperate with Sieyès in dissolving the legislative councils in brumaire Year VIII (November 1799), but he, rather than his would-be patron, had the decisive voice in framing the new authoritarian constitution which was promulgated after a hasty referendum in December. It invested Napoleon with practically limitless powers as First Consul of the Republic. ‘Citizens,’ he proclaimed, ‘the Revolution is established on the principles with which it began. It is over.’ …… Napoleonic rule would bring its own problems and contradictions, but it endured because it began by resolving others that had torn the country apart for more than a decade.

原书信息:Doyle, William, The French Revolution: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd edn, Very Short Introductions (Oxford, 2019; online edn, Oxford Academic, 21 Nov. 2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198840077.001.0001