原书及其作者:牛津通识读本系列丛书,或者“A Very Short Introduction series”,一个非常高质量的学科入门读本系列。16到17世纪左右,这段宗教改革的故事从近乎偏执于原教旨的圣经解读出发,最终却落在了催生多元社会的终点上。

Chapter 1 Reformations

A German event

P11

But everything about the tale is significant: the intensity of the medieval cult of the saints, the combined quest for material and spiritual salvation, the setting in Germany.

宗教改革的背景:中世纪的圣人崇拜非常泛滥,遇事不决就向圣人祈祷,在今天看来甚至已经近于迷信;宗教不仅是种心灵慰藉,而被视为解决一切生活问题的神秘力量来源;以及以德国为发源地。

P11

Asking why the Reformation started in Germany is a bit like asking why the Communist Revolution started in Russia, or the telephone was invented in America – it happened there because it happened there. Some important ‘preconditions’ seem absent.

与想象不同,德国在1500年前后的几十年来都是不出什么异端的干净区,(heresy-free)极其少见对教会权威的挑战。

P11-12

What was distinctive was its political structure. Unlike the emergent national monarchies of France, England, and Spain, Germany was politically fragmented – a patchwork of petty princedoms, ecclesiastical territories, and self-governing cities, under the nominal suzerainty of the grandly named Holy Roman Emperor. The office was elective, the emperor chosen by seven territorial ‘Electors’ (including three archbishops).

特殊之处在于,和当时欧洲普遍的君主专制不同,德国的政治版图是离散的,亲王国、教会领土、自治城市林立,国事由代表会议商讨决定,代表们由选举产生。

P12

Germans compensated for political weakness with a passionate cultural and linguistic nationalism. …… The vacuum of centralized control in Germany meant that popes retained greater power to appoint to ecclesiastical offices, and, via the prince-bishops, to extract taxation from the populace – always a fertile source of bitterness. Anticlericalism – an antipathy to the political power of the clergy – does not equate to rejection of Church teachings. All the evidence suggests that early 16th-century Germany was a pious and orthodox Catholic society. But national and anticlerical resentments abounded, and they found their voice in Luther.

政治上散漫,那么国族认同就由热情活跃的语言和文化认同而维系。

政治力量上留出了薄弱的真空,这部分空间就由教会势力拿走了。在一群散漫的主体中间,不受制约的教会势力自然也就多敛赋税,成为民怨缓慢积攒的源头。

The Luther affair

P13

There was in 1517 no blueprint to reform the Church, no foreseeable outcome. Political circumstances, combined with Luther’s stubbornness and eventual willingness to think the unthinkable, allowed it all to get out of hand.

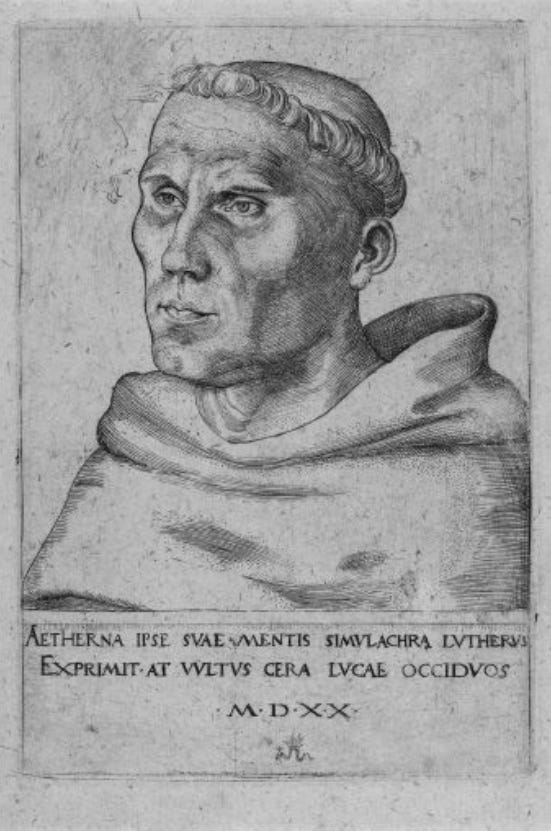

1957.10.31,马丁·路德(Martin Luther)在维滕贝格城堡附近的教堂门口上贴出自己为一场大学内神学学术辩论准备的95条论纲清单(Ninety-Five Theres)。这个节点即被历史学家选为中世纪结束与新教改革开始的标志点。

但实际情况没那么戏剧化,就像许多重大历史浪潮被后人选定的起止点一样,当时完全没什么人觉得这份清单和其他任何教授课纲或学生论文有什么不同。在一个宽松的学术环境里,这份往后衍生出无数波折的清单就这么平平无奇的贴着了。

P15

Indulgences were a certificate remitting some of the punishment due in purgatory in exchange for performance of a good work (they were originally developed as an inducement for people to go on crusade) or giving money to a good cause. Popes argued that, as heads of the Church on earth, they could draw on the ‘surplus’ good deeds of the saints to underwrite indulgences. The system had a coherent underlying logic, but it was open to abuse, and had been criticized by some thinkers, especially humanists, long before Luther.

最初的争议源起于赎罪券(indulgence),虽然在当时的理论里,捐善行来换取自己灵魂的净化算是逻辑自洽,问题在于这个体系十分方便滥用。好巧不巧在地碰上一个腐败的执行者时,争议爆发,然后被隔岸观火的教皇视为“不过是修士间的普通吵吵”。

此时的路德还只是一个平平无奇的大学教授,但关于赎罪券的争论给了他关于救赎的思考以养分。

‘as soon as the coin in the coffer rings, a soul from purgatory to heaven spring’ — an advertising jingle of oppose indulgence by a friar, Johan Tetzel.

P15

Luther meanwhile was edging towards a momentous conclusion – if the Church and pope could or would not reform an evident abuse like indulgences, then something must be wrong with the entire structure of authority and theology. For some years Luther had been nurturing doubts about the elaborate ritual mechanisms for acquiring ‘merit’ in the eyes of God, and coming to the view that faith alone was sufficient for salvation.

随着路德思考的发展,他开始质疑教会的权威,认为教会也是会犯错的,实际上把教会和教皇从不可质疑的“人间神”宝座上拉了下来。那么,就只有回归圣经能成为信仰生活的唯一准则了。

这些观点被斥为歇斯底里的激进,路德被教皇逐出教会,无路可回头,他的倡议和改革也就动作更大。

P16

One of them was Luther’s territorial prince: Elector Frederick ‘the Wise’ of Saxony. Frederick was thoroughly old-fashioned in religion, but immensely proud of the university he had founded, and of its new superstar professor. He thus protected Martin Luther from his enemies. …… In the course of these travails, Luther had become a celebrity, and a German national hero.

当时各家分立的政治局势和路德自己的投胎彩票,让他免于过早的被教会弹压,大展自己的风骨,甚至还在避风头期间完成了《新约》的德文白话翻译。(基督教的《圣经》分为《新约》和《旧约》两部分)

‘here I stand, I can do no other’ — a veritable slogan of individual freedom and modernity by Luther.

P17

The co-incidence of Luther’s protest and the new technology of the printing press seemed to later 16th-century Protestants a veritable providence of God. In fact, printing was not so new.

路德恰好生在欧洲的印刷技术已经成型,但是还没有流行开的时候。

在那以前的印刷业主要出版天主教的神学作品,而路德的横空出世让印刷业突然就从只承载既成事实的工具变成了广传思想的载体。

又一次,分散的德国政治局势帮了路德,这一背景使得印刷中心也同样分散,因而难以查封。

Zwingli and the beginnings of radicalism

P17-18

The protest against Rome was not just Luther’s affair. He was the prophet, rather than in any concrete sense the leader of the movement, and the Reformation involved discrete reformations from its earliest stages. Events in the Swiss city of Zürich bear this out. The moving figure here was the resident preacher at the principal town church, Huldrych Zwingli (1484– 1531), who by his own account ‘began to preach the Gospel of Christ in 1516 long before anyone in our region had ever heard of Luther’.

乌尔里希·慈运理(Huldrych Zwingli)有更深厚的人文主义背景(不是现代话语里的人文主义),并且也深为教会内部的蒙昧状态而不满。

慈运理和路德一样都非常看重基督教中的“自由”概念,主张只有圣经直书的内容才是不可违背的,教会定出来的繁文缛节都是妄想。

P18

This was a pattern of ‘urban reformation’ replicated across much of Germany and Switzerland in the 1520s, as mini-Luthers and mini-Zwinglis sprang up to demand reform from the pulpit, and town magistrates, sensing the popular mood, decided to recognize their demands.

早在路德显赫之前,慈运理就在当地市民的支持下完成了许多简化虚文的改革(瑞士苏黎世),许多地方意见领袖也是如此。宗教改革的初期是到处都有此起彼伏的改革和改革呼声,路德作为标志性的改革发起者并不是运动的全线领导者。

P18-19

Change was swift in Zürich, but not quick enough for some. A group around the humanist Konrad Grebel felt that Zwingli was acting too slowly in getting rid of statues of the saints, and broke decisively with him in 1523. Their slogan of ‘not waiting for the magistrate’ put them at odds with all who wanted the implementation of Reformation to be an orderly and official business.

慈运理在苏黎世引领的改革其实已经节奏比较快了,但是仍然催生了更加坚持圣经原教旨的人嫌慢,这部分人也就让自己成为了少数派。他们组成了以康拉德·格列伯(Konrad Grebel)为中心的再洗礼派(Anabaptist),“再洗礼派”逐渐成为一个泛指所有人眼中的激进分子的词。

路德此时在躲风头并翻译白话《新约》之后再出,也和他认为过于狂热的同志产生冲突。

Popular reformation and the Peasants’ War

P19-20

Luther had sown the wind; now he would reap the whirlwind. So at least his Catholic enemies claimed, arguing that departure from the time-honoured teachings and traditions of the Universal Church would lead inevitably to anarchy and rebellion. Events in the mid-1520s suggested they had a point. Luther was no social revolutionary. …… But what is preached and what is heard are not necessarily the same.

路德从改革精神枷锁和宗教礼节出发,一开始并未想要动摇当时社会的政治经济基础,但是宗教改革是因为引起了人心所向的共鸣而得声势,哪里能止步于发起者的个人意愿边界。

中世纪的宗教组织和社会纤维根本没有彼此可分,于是宗教改革冲击传统而造成的当时乱象自然也就成了天主教世界指摘改革的一大论据。

P20

Studies of popular printed propaganda for the Reformation – broadsheets and woodcut prints – suggest that serious attempts to get across Luther’s more complex theological ideas were usually sacrificed in favour of broad satirical attacks on the Catholic clergy and hierarchy, with monks and friars depicted as ravening wolves, the pope as a ferocious dragon.

随着运动升温,普通民众各自从路德的讲道之中取用自己能理解和能共鸣的部分、天主教和新教的双方对垒逐渐变成漫画化的诋毁攻击。在这之中,对于路德真正本源神学理念的探究往往是第一个被牺牲的。

P20

For all that the early Reformation is sometimes described as an ‘urban event’, it was in the countryside and among the peasants (the overwhelming majority of the population) that the teachings of the reformers were most obviously domesticated to an agenda of social and economic aspiration.

城市人为抽象理论而争,而到了占人口绝大多数而受压已久的农村和农民之中,理论上的讲道引发了人们对于原本没有合适思考表达载体的的社会和经济改革的期望。此前的零星反抗开始集中成其气候,从以往的“平民的革命”(revolution of the common man)变成了大规模的“农民战争”。(Peasants’ War)

社会运动都需要相应的语言载体,来讨论问题和动员参与,在有宗教传统的地方,这种载体的角色很多就由原本属灵的语言承担了。

看到灵性的改革竟引起战争,路德本人出版作品敦促镇压这种他眼里的血腥发展,而各地政权本来不需要鼓励也有充足的动力去行血腥镇压了。

‘Christ has delivered and redeemed us all… by the shedding of His precious blood‘ — quote from the Twelve Articles adopted by a combined rebel army.

German politics and princely reformation

P21

A staple of early pamphlets was the figure of Karsthans, the cocky Lutheran peasant, who out-argues the priests and university dons. After 1525, the Reformation was ‘tamed’, reform became respectable, and Karsthans disappeared. The dissociation of Lutheranism from social radicalism opened the door for princes to adopt what its adherents now called the ‘evangelical’ faith.

1525年后,宗教改革支持者的形象从狂妄自大的下层人逐渐变得能上得台面和不极端了起来,许多王公贵胄也可以体面的皈依路德宗。

新教和天主教、东正教略有不同,本身是天主教和东正教以外教派的统称,这里提到的路德宗(Lutheranism)就是新教宗派。

P22

In the meantime, official reformations were starting to take place outside of Germany and Switzerland, notably in the Scandinavian kingdoms. …… Kings, as well as peasants, could select what they fancied from the menu of Reformation ideas.

同时,在德国和瑞士以外的地方,许多地区的统治者开始推行宗教改革,改信新教。但他们中的很多人对于路德喋喋不休的神学理论也没什么兴趣,时常自取改革事项里符合自己需求的部分,比如解散修道院。

P23

…… compromise at home looked sensible, a view shared by Catholic German princes who considered stable government by heretics preferable to the anarchy unleashed by the Peasants’ War.

在当时的德国国内,统治者查尔斯五世(Charles Ⅴ)自认为天主教世界的坚定卫道者,因而让改革陷入困境,但是由于卫道者们八方受敌的时政环境,容忍异端而保证政治稳定成为了两害相权取其轻的选项。

因此许多统治者基于政治权衡而对新教采取了比较宽容的态度。等到了1529,环境转安,当他们再想收紧政策时,遇到了六个王子和十四个代表的反对。他们签署的反对声明(protestation)从此创造出了“新教(Protestant)”这个新词和新的政治身份。

P23

Protestants banded together against the fear the empire was about to strike back. Under the leadership of Philip of Hesse and John of Saxony, a defensive alliance was concluded in the Thuringian town of Schmalkalden in 1531. This was a political complement to the Augsburg Confession of the previous year, an agreed statement of core Lutheran doctrine, drawn up by Luther’s younger collaborator, Philip Melanchthon.

到后续的1530和40年代,出于可能遭遇天主教统治者反击的恐惧,新教徒通过签署教义声明(Augsburg Confession)和形成防御联盟达成了一定的团结。但是不同地区的新教势力总体还是分散的,比如瑞士和慈运理并不接受这份信纲。

P24

Pride comes before a fall. The magnitude of Charles’s victory alarmed the German Catholic princes, who, fearing for their autonomy, backed away from their military alliance. Several Protestant states resumed the offensive in 1552, supported by the French Catholic king, Henry II, who saw an opportunity to make mischief. …… The mandates of the 1555 Peace of Augsburg are usually summed up in the Latin tag, cuius regio, eius religio (‘whoever your ruler is, that’s your religion’). Princes within the empire were free either to retain Catholicism or adopt the Augsburg Confession. Cities could profess Lutheranism on condition of allowing Catholic worship as well. Religious divisions were thus recognized and institutionalized, and the Reformation was saved in Germany.

到了50年代,查理五世和其他卫道者基于外部压力形成的军事联盟破裂。在新教国家和天主教国家的拉锯之中,各国内的宗教分歧实际上得到制度承认。

对于这样的相互妥协,反而是挺过危机的路德宗变得僵化和教条,面对妥协争吵不休。在路德门人争吵过程中,路德宗逐渐淡出了宗教改革的中心,改革经历新生。

Calvin, Geneva, and the Second Reformation

P27

One of these (French refugee who were escaping from a Catholic restoration at the time), the Scot John Knox, liked what he saw, considering Geneva ‘the most perfect school of Christ that ever was in this earth since the days of the Apostles’. There were other places where Christ was truly preached, but none for ‘manners and religion to be so sincerely reformed’. Posterity has been less effusive, inclined to regard Calvinist Geneva as dour and repressive, a theocratic police state.

相比性格戏剧化的路德,受过传统律师训练的加尔文(John Calvin)神学理论更为严谨、稳定,由他在日内瓦(Geneva)开展的宗教改革既是更加完美成熟的,也是更加道德死板的。

P28

A minority group (Huguenots), blatantly defying the wishes of the French crown, required a militant and self-righteous ideology, and a tight organizing structure: Calvinism supplied both.

加尔文的日内瓦很快就成为了横扫欧洲的“二次改革”的中心(Second Reformation)。和路德相同的是,大潮由他启发,但很大程度上不是他所计划和导演的。

加尔文产生直接影响最大的方面在于催发了法国胡格诺派(Huguenots)新教徒的组织和思想发展。加尔文为这个少数派提供了军事化和自我正当化的思想基础。

时值法国政治不稳,加上贵族寄希望于通过资助宗教改革来颠覆国家,宗教分裂最终带来了法国宗教战争(French War of Religion),直至以政治稳定为重的亨利四世继位,通过颁布《南特法令》(Henry’s 1598 Edict of Nantes)从制度上允许了宗教分歧。(在天主教法国内允许胡格诺派礼拜仪式)

P29

The result was open revolt (1566), and an almost universal revulsion, on the part of Catholics as well as Protestants, against the brutal methods of the Duke of Alva’s Spanish army sent to repress it. Increasingly, however, Calvinism could paint itself as the creed of patriotic resistance, particularly after it was adopted by the military and political leader of the revolt, William of Orange.

加尔文主义(Calvinism)在同一世纪的另一场武装抗争中也见影响。西班牙治下的荷兰(Netherlands)由于统治者的无知专横掀起了公开叛乱,在战争中天主教、新教、加尔文主义同台竞技,但是加尔文主义迅速占了上风。

叛乱后,荷兰沿着宗教断层线分裂为了信奉新教的北部(Dutch Republic)和南部信奉天主教的西班牙属荷兰,后来演变为比利时。(Belgium)

P30-32

Calvinism was a protean beast. It shaped the Reformation in all parts of the British Isles, but produced different shapes in each of them. …… As elsewhere in Europe (here means Europe out of Germany), a selling point of the Calvinist system was its malleability. German princely Calvinism had a politically authoritarian style – no synods or general assemblies here. Relations in Germany between Lutherans and Calvinists remained tense at best. But it was Calvinism that stood to the fore in the era’s greatest ideological conflict, confrontation with the forces of resurgent Catholicism.

Catholic responses

P33

But force is by no means the whole story. Catholicism remade itself in the course of its own reformation, drawing on its historic strengths but also exposing itself to the shock of the new. The process began in earnest at the Council of Trent (1545–63).

在16世纪初,新教还没铺开的时候,天主教一度通过自身的改革和原本掌握的军事力量稳占上风。

P34

Perhaps the most crucial reform was the order for all dioceses to set up seminaries for the training of clergy, a distinctly haphazard process in the Middle Ages. The aspiration for a disciplined and educated priesthood was a cornerstone of Catholic reform.

天主教内部所有派别的改革者一致认为,一个统一的理事会(a general council)是当时问题的主要出路,但是由于弥合派系宗教分歧又会触碰到当时宗教和政治上的既得利益集团,导致这种和解被一拖再拖,错失良机。

但是一个统一的会议(council)最终还是在意大利特伦特召开了(the Council of Trent),前后几次的议程虽然对最大的重点绕着走,其他方面的实事还是做了不少的。

明确教义(formulating definitions of Catholic doctrine),规范主教的行为界限,让许多已经由成熟而腐烂的制度性问题重回正轨,甚至还为培养稳定高素质的神职人员建立了基础设施。这些措施让天主教日渐区别于新教。

P34-35

Trent inaugurated a new way of being Catholic, expressed in the Latinized adjective ‘Tridentine’. When the Council wrapped up, the process of Catholic reform still had a long way to go, but the achievements were undeniable. The clarification of Catholic doctrine on virtually all contested issues created a unified template of belief for a single Roman Catholic Church, superseding the woollier ‘Catholicisms’ which had co-existed in pre-Reformation Europe.

以阻止神职人员滥权为出发点,特伦特会议在平抑牧师和主教的权责之余,实际上起到了加强教皇权威的效果。

此举让文艺复兴以来教会荒唐颓废的氛围一扫而空。除了实权加强,后续几位教皇的简朴修身让教皇职位的声誉有了相当的回复。

但是这部分的中央管理集权,和一系列加强教皇权力集中的文件和机关建构,与改革精神背道而驰。(Counter-Reformation)

The Thirty Years War and after

P37

The numerous regional confrontations between Reformation and Counter-Reformation were after 1618 subsumed into a general and bloody conflagration, pitting the Spanish and Austrian Habsburgs, and a Catholic League headed by Duke Maximilian of Bavaria, against the Protestant states of Germany, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia (James I’s England, to the dismay of Puritans, held aloof). The Thirty Years War began as a war of religion, though it didn’t end that way.

P41

The outcome was repression and rebellion, a wave of expulsions and insincere conversions, and a movement of exiles across borders to nurse bitterness and stoke the fears of their hosts. For a century and a half, reformations had been the chief motor of European political and cultural life. They had not quite exhausted that function, as the age of Enlightenment dawned.

参考文献

Marshall, P. (2009). The Reformation: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923131-7